In June 2020, Paul Riekert had emergency surgery. He lived to tell the tale.

(I strongly suggest you read Part 1 and Part 2 if you haven’t yet.)

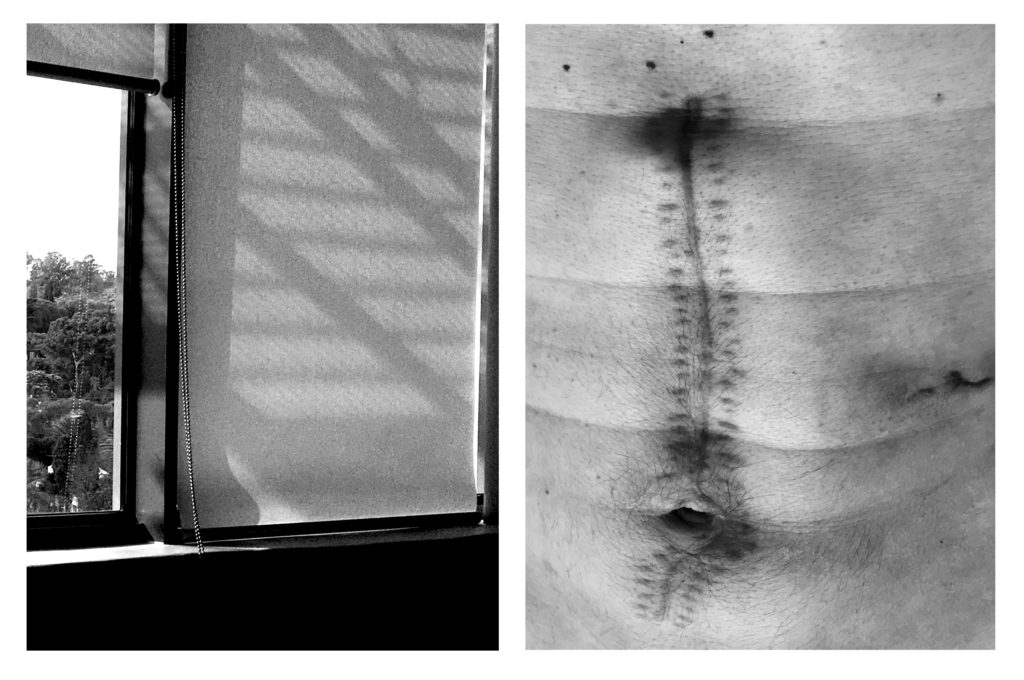

The wounds have healed. When I run my fingers over the laparotomy scar, I can feel two rows of tiny staple scars next to the big one in the middle. Like metal plates that had been joined by welding and riveting. Do you ever touch your scars? Try to imagine what they must feel like to other people?

There’s still a bit of pain sometimes; it’s random but short-lived. I’m getting used to suddenly seeing the scar in the mirror. It’s my scar, after all, and I like scars. But it still feels a bit alien.

I remember my surprise when they removed the long, heavy plaster for the first time. I certainly did not expect a row of staples from the tip of my sternum past my navel. The first time I saw it, from that angle, it resembled the big front zipper of a bikers’ jacket. When I woke up in the ICU, no-one had an information session with me, explaining things. No. They grudgingly told me the basics, but, for the rest, it was one big surprise package.

On my fourth or fifth day in hell, I think, the dieticians sent to me: clear liquids like fruit juice and chicken broth. The horrible pipe, which was meant to vacuum-suck my stomach empty, and protruded from my nose, was taken out. The nil-per-mouth-rule was revoked! It sounds like a really humble upgrade – clear liquids – but it was of major importance. Despite being fed and hydrated intravenously up to that point, I was hungry and thirsty most of the time. It was incredible to feel water in my mouth again.

Within about five days I was allowed solid food. Sad and bland solid food, but at least stuff you can chew, that vaguely tasted like something.

After many days in the ICU, could have been six or so, I stopped wishing to leave the ICU immediately. I resigned myself to receiving intensive care indefinitely. Bring it on. It was the only way to cope with what was going on: accept that artificial milieu as normal and move on. Don’t fight, feel it. It worked, mostly, although at times a debilitating air of despondency would sneak in. Stuck. Stuck.

The physiotherapists gently forced me to get up and go for a walk every day. I could see the outside world, get stronger, and have shards of normal conversation. It would make me feel better; bring an air of solidity to those dismal 24-hour stretches without darkness or daylight.

On my tenth day in hell, incredible things happened.

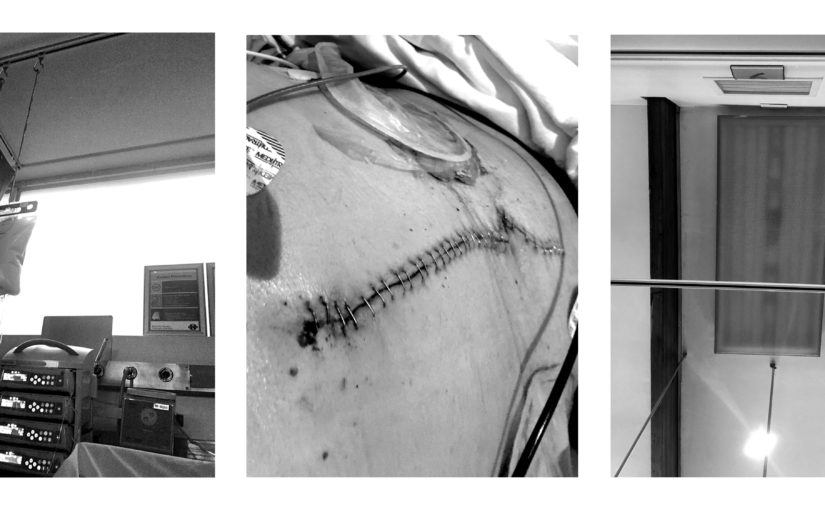

The external drip port, which was inserted into five different blood vessels, was taken out. No more intravenous stuff! Then the cardiovascular monitoring cables were disconnected. I could move a bit! And shortly thereafter, senior personnel announced that I was being moved out of the ICU. My personal belongings in the bedside metal cupboard were stuffed into a big clear plastic bag and put on the bed near my feet. My oxygen tube was disconnected from the wall unit and connected to a portable cylinder. All these sure signs…and yet it was difficult to believe that I was finally getting out of there, that wherever I was going would be better. But when a cheerful porter arrived, I realised that it was actually going to happen. I was being wheeled out of the ICU. Just like that.

The porter pushed the bed at what seemed like breakneck speed. We travelled along the standard tall and wide corridors for most of the journey. At some point, after using a huge lift, the corridors became smaller, framed “art” started appearing on walls, and sections were clad in marble.

“This is the suburbs -part of the hospital”, the porter said, before pushing my bed into a small empty ward and disappearing.

I couldn’t believe it.

He was only half-joking. It was a small room, a few stories up, with huge windows and a 170-degree view. Sunlight was streaming in. I could see an old suburb with wide tree-lined streets below. A biggish television was mounted on the wall in front of me. To the left was an open door that led to a bathroom. All of it completely private. With no drips and sensors and cables and tubes attached to me. Yes! It seemed extremely luxurious compared to the hellish ICU; like I had hit the jackpot. Despite the pain, I got up out of bed and stood by the window. I could feel the sunlight on my face and arms. I was alive.

I experienced an enormous sense of relief. It was so intense that the effects lasted for more than an hour. Pure, unadulterated joy.

It was such a novelty to be able to move about freely, without all the attachments. I couldn’t exactly do star jumps yet – I still had pain-inducing drainage systems with bags hanging from holes below my rib cage and a long, tight row of staples embedded in me – but to have a choice how and when to move was amazing. I started wondering why I was put in a private ward. Was it for my benefit, or for the benefit of others? Who was being protected against whom? Both options seemed hilarious.

For the first time in ten days, I could take a shower. (As opposed to being bullied into an involuntary “bed bath”.) I received specific instructions NOT to get the wounds wet; luckily the bathroom was geared for that sort of thing, with adjustable horizontal showerheads.

Being confronted with a mirror was a bit of a shock. I had lost weight. And I didn’t have any to spare. I looked really thin, almost emaciated. Apart from the serious plasters and drainage bags, I had an array of small wounds and scabs on my arms and chest from intravenous gear. Like shrapnel wounds. I had a full, mostly grey beard, with an almost entirely black moustache, and my hair was the longest it had been in 24 years. I could do with a tonsor.

Instead, I got a dietician, who was kind enough to arrange some cheese and biscuits for me. Plain salty biscuits and humble cheddar cheese. To taste something that was engineered to taste good, after all the bland liquids and food, was euphoric. It had a healing effect.

This is a concept that only certain medical personnel seem to grasp: if you feel better, you heal better. Most of the medical personnel I encountered fit this category. Kindness came into it at some point. Others skip this chapter completely. They see you as a meatbag, a soft machine at most, that has to have the right readings – on the machines and according to, say, the blood tests or radiology results. Whether the meatbag is uncomfortable, cold, in pain or experiencing mental anguish, doesn’t really concern them. At the extreme end of this scale are the sadists, who love to torture the helpless patients, postponing their painkillers, or denying them water, or do whatever would cause them short-term discomfort.

In this vein, the two doctors, whose exact details shall remain vague, had very different approaches. The one was a delight: rational, reasonable and friendly. The other one was the exact opposite. The bastard had the bedside manner of a carnivorous insect. I wanted to choke the crap out of him from the word go. The two of them had complete control over my stay in the medical facility: where I should be, what food and drugs I should consume, when I am officially getting better, and so on. They visited daily. Some days both of them would pitch at the same time. It never lasted longer than two minutes, yet they both billed me thousands for each “visit”. I loathe such obvious and shameless milking. But I shouldn’t be complaining, I guess. They did perform the most important parts of their duties in an expert manner, otherwise I wouldn’t be sitting here, very much alive, complaining about stuff.

The few humble improvements in my daily existence made me feel human again, and less like a meatbag. For the next few days, I made the most of the setting, enjoying the view, the sunshine, the starry night sky, the privacy, the improved menu. The semblance of normality also triggered an increased longing to go home. To re-enter the existence I’d been violently plucked from.

The medical personnel became very interested in the drainage bags. After absent-mindedly emptying them before, they suddenly started measuring their contents in millilitres. There was less liquid in them every day. It seemed that, when those bags stayed empty, I could go home.

About three days later my “favourite” doctor signed the discharge form. Unceremoniously. And barked orders at an incredibly tall nurse who spoke with a Caribbean accent. She took out half the staples, every second one. Unbelievably, she was cracking jokes while she worked. Good ones, too. Then she proceeded to detach both drainage systems embedded in my abdomen, removing the bags too. It was really painful – a return of the fiery pain I felt right after the operation. I wanted to protest (or rather, scream in anguish and demand anaesthetic), but then I thought: just get this over with, keep quiet, just grin and bear it. Don’t give them any reason to keep you in this place for a second longer. I was ice cold and sweating from handling the pain by the time she was finished.

She gave me instructions, handed me a pack of “dressings” for all the wounds, and excused herself.

I got dressed, in “real” clothes, gathered my few belongings, then took a moment and sat on the chair next to the bed. It felt strange. A bit overwhelming. I was looking forward to that moment for many days, and there it was. Action.

I was slowly winding my way through the labyrinth, finally turning into the widest, tallest, longest hallway that would take me straight to the outside world. On my right, about halfway down, was the entrance to the ICU. It made me walk faster. At the end of the hallway, down a staircase, I entered the glass-and-aluminium foyer of the hospital. Many people were cueing at the entrance, being screened for Covid-19, but the exit was clear. The automatic glass doors opened in front of me and I stepped into glorious sunlight. I made it!

I was among the living again! I had been to hell and I made it back.